Gold, Frankincense and Myrrh

Shopping for Christmas treasures in Oman

Every child

growing up in the West knows the story of the birth of Jesus and how the three wise men, the magi, brought the baby in the manger gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.

We all have a fair idea of what gold is, but frankincense and myrrh are less familiar. They’re sometimes used as ingredients in fragrance or in beauty potions, but most people would not realise that they are aromatic resins harvested from low trees found in the cooler areas of the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa.

You will find gold, frankincense and myrrh in abundance in the magical country of Oman, which occupies the corner of the Arabian Peninsula on the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman, adjoining Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

These treasures of the ancient world can be found in the shops of the gold souk at Mutrah, the old part of the capital Muscat, where dozens of glittering 21-carat bracelets and extravagant neck pieces hang tantalising in each window display, in the rocky desert in the Dhofar region where the picturesque frankincense trees grow and in the wonderfully exotic souk in the southern city of Salalah where tubs of crystallised myrrh are sold.

The fragrance of frankincense fills the air the minute you step off the plane. A milky white resin that forms pale rocks, frankincense is burnt on charcoal in burners called majmar and these are found in the entrance of almost every building, with the delicate white smoke scenting humble homes and grand hotels alike, so that it all mingles in the atmosphere, enveloping you in its sweet, citrussy perfume.

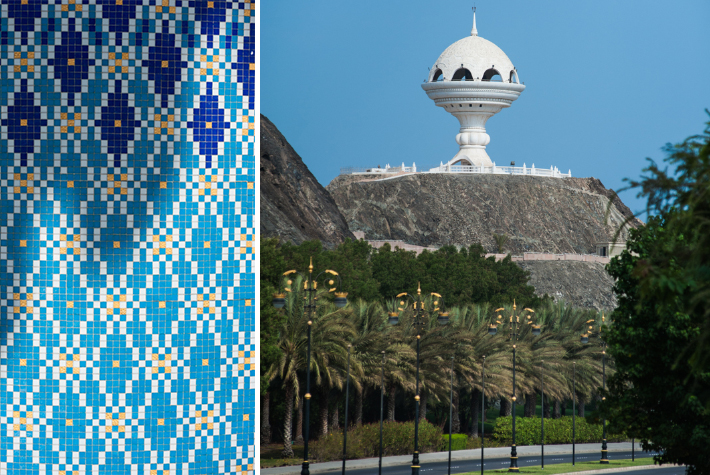

You can’t miss the enormous and ornate stone majmar that’s one of Muscat’s landmarks. High on one of the craggy mountain peaks that surround the city, the oversized incense burner overlooks the gold and blue-tiled palace of the new Sultan Haitham bin Tariq Al Said.

I love frankincense, ever since discovering it in Muscat on a visit eight years ago. I brought back a small sack.

From the majmar you can experience fabulous views across the gulf and the lovely corniche at Mutrah, the old town of Muscat, which is lined with houses dating back to the Portuguese occupation of 1515-1650. It symbolises the Omani’s love for the aromatic resin, which the nation has traded for over 5000 years and was once a major source of riches, until the trade went into decline three centuries ago, when the Portuguese took over the trade routes and the Roman Catholic Church began to buy the cheaper Somalian product.

I love frankincense, ever since discovering it in Muscat on a visit eight years ago. I brought back a small sack of it and every time I burn it I am transported back to the Mutrah souk, where it is sold in kilogram packs. Frankincense is also edible, with antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties, a traditional remedy for everything from toothache to leprosy. Scientists are currently investigating it as a cure for some cancers, arthritis and asthma.

The highest quality frankincense still comes from Oman, in the Dhofar region in the south, where the summer monsoon or khareef, turns the mountains around the main city, Salalah, lush and green as Ireland. The ancient Frankincense Trail, where the resin has been grown, harvested and shipped for millennia, is now preserved by UNESCO as a World Heritage site.

We flew to Salalah from Muscat, a flying time about ninety minutes on frequent regular services by Oman Air. Salalah is extremely popular in the hotter months with people in the Gulf States because the weather is cooler by at least 10 degrees Celsius and the frequent rains and heavy fogs are a novelty for people who live in climates where it barely ever rains. From October-April, Europeans fly directly into Salalah on charter for its perfect, warm weather.

The region is blessed with long, white, mostly empty beaches lapped by the turquoise Indian Ocean. The mountain ranges during the khareef are certainly emerald green, reminding some of Ireland, but the landscape soon turns to rocky desert behind the mountains and then to the spectacular sand dunes of the Arabian Empty Quarter.

Our guide, Mosallem, drives us 40 km to see the frankincense trees growing in the UNESCO reserve in the rocky desert in the Wadi Dawkah. The Boswellia Sacra trees are low-growing and twisted, with small white, yellow or red-centered flowers. They don’t produce sap in humidity, so the dry desert areas are perfect for cultivation. Hardy trees, they don’t need much water, with roots than can go down 50 metres.

The trees only start producing when they are eight to ten years old. The bark is slashed, allowing ‘tears’ or drops or resin to ooze. The resin is collected and left to harden. Trees are tapped two or three times a year but over-exploitation has resulted in frankincense populations declining, hence the UNESCO preservation.

Old trader’s houses, including the old souk, have been left to crumble in situ, with beautiful old doors falling off their hinges.

Near Wadi Dawkah is a magnificent archaeological ruin of the old port of Khor Rori or Sumharam, where the Queen of Sheba once kept a palace and which sits in a picturesque spot overlooking the sea of Oman. The frankincense was transported by camel or donkey to warehouses in this fortified city, where it was stored and later shipped to places as far as China, Africa, the Mediterranean, India and Zanzibar.

The structure of the building, dating back to the 2nd Century BC, is amazingly well preserved, and restoration work is being done with the help of the University of Pisa. Camels still seek it out, to roam to nibble on the lush grass beside the inlet but, unlike many world architectural sites of this significance, there are few tourists – in September, at least.

Evidence of the decline of the trade can be found in the fascinating town of Mirbat, an export port for frankincense, Arabian horses and slaves since the 3rd Century BC. While part of the town is still occupied, mostly by immigrants from Bangladesh and India, whole neighbourhoods of once handsome 19th Century trader’s houses, including the old souk, have been left to crumble in situ, with beautiful old doors falling off their hinges and tiled bathrooms open to the elements. Visitors to the city can walk through dozens of old houses unhindered, in what amounts to a ghost town.

Frankincense was shipped from here up until the 1960s. Now, the town is essential visiting if you’re interested in architecture and also for the simple fish restaurants at the port, where you can feast on grilled fish for very little money, while watching giant turtles frolic by the shore.

If you wish to know more, the Museum of the Frankincense Land in Salalah, next door to the Al-Baleed Architectural Park, a pre-Islamic settlement, is a beautifully designed new museum which answers all your questions about frankincense, including the different grades of quality. It also houses a wonderful Maritime Hall with intricate models of the various ships, such as the dhoni and baghla, built by fishermen and traders in this seafaring nation. (Sinbad was an Omani, they claim.) In a boutique nearby, local women will sell you medicinal oils and waters they have created from distilling the frankincense.

In Salalah, the frankincense souk is a vibrant, relatively hassle-free place where the shopkeepers will ply you with everything from beautiful tasselled massar (turban scarves) made by local women to heavily fragrant Arabic perfumes and various grades of frankincense, of which the pale green is the most prized. They were selling this at about $AUD75-90 per kilo with the lesser grades considerably cheaper.

There are dozens of shops down atmospheric little alleys selling incredibly elaborate gold pieces from headdresses to bangles.

I also looked for myrrh here, and a shopkeeper sold me a little tub for about $AUD3. The best myrrh is grown in Yemen, but Salalah is only about 150 km from the Yemen border and occasionally trees are cultivated. The myrrh tree, Commiphora myrrha, is pricklier than the frankincense and the resin is a richer brown colour like brown sugar. The process for harvesting the sap is identical.

Myrrh doesn’t have much of a fragrance, although it is sometimes burnt with frankincense. The shopkeeper who sold it to me told me it was more often used as a medicine, dropped into water to drink to cure upset stomachs. In ancient times, myrrh was used in embalming ceremonies, symbolising death, while frankincense symbolised spirituality. (The gold that the infant Jesus was given symbolised royalty, power and influence.)

With sacks of frankincense and a little myrrh in my suitcase, we flew back to Muscat in search of gold, where we spent an afternoon in the gold souk, on the corniche at Mutrah, the old town of Muscat. It’s one of my favourite bazaars in the world for its shops selling genuine antique Bedouin silver as well as gold.

There are dozens of shops down atmospheric little alleys selling incredibly elaborate gold pieces from headdresses to bangles. I wondered who would buy all this gold, but our guide Juma tells me Omani women are given gold jewellery from an early age – simple things such as hooped earrings or bracelets. The largest gold purchases happen when they become engaged to be married, for their dowries.

The gold is imported from Dubai. The rates are seasonal. The Omanis buy a lot of gold during their summer holidays in July and August, so the prices in September are quite reasonable. I was quoted 13.5 rial (about $AUD38) a gram for 21 carat, including the manufacture.

Elsewhere in Muscat, there’s gold everywhere you look, from the dome of the majestic Sultan Qaboos mosque to the enormous statue of a gold coffee pot that sits in the middle of one of the city’s manicured traffic roundabouts. Even the Amouage factory, which sells Oman’s famous, pricey fragrances (‘Gold’ was their very first perfume), has a splashing pool outside lined with shimmering gold tiles.

The scent of frankincense, the undercurrents of myrrh, the gold domes glittering in the sun – Oman might be the perfect place for modern magi to visit at Christmas.

For further information visit Oman Tourism

WHERE TO STAY

The Chedi Muscat

Muscat’s most beautiful resort hotel is situated on the Gulf of Oman in central Muscat, amid 21 acres of gardens, reflective pools and six restaurants and bars. Three swimming pools, one at 103 metres (the longest in the Middle East), superb international food (executive sous chef David Pooley is from Sydney) and one of the most glamorous spas we’ve experienced make this hotel the coolest place in town. Club suites include free luxury airport transfers and laundry as well as a private lounge. We can’t stop raving. The Chedi Muscat

Al Bustan Palace by Ritz Carlton, Muscat

Muscat’s first international hotel occupies an unattractive high-rise building (unusual for low-rise Muscat) by the sea but lovely landscaped gardens and a renovation by Ritz Carlton has upped the ante. Jump into the pool directly from the deck of your poolside room. Al Bustan Palace.

Juweira Boutique Hotel, Salalah

This 83-room marina-front hotel is part of a new complex on 16 million square metres that will soon house five hotels, villas, shops and a golf course. Rooms are large, the seafood restaurant serves fabulous fresh giant shrimp and the white sand beach is 17km long. Juweira Hotel.

GETTING THERE

We flew from Kuala Lumpur courtesy of Oman Air and its excellent Business Class, which offers large lie-flat beds, truly delicious food and some of the most attentive and friendly service we’ve found in the skies. We also flew from Muscat to Salalah on Oman Air’s domestic service, which is efficient and comfortable.

Mr and Mrs Amos were guests of Oman Tourism and Oman Air.

Love the detail in the writing Lee. I saw you interviewed by Deborah Hutton on the entertainment channel with Virgin. That’s how I found out about Mr&MrsAmos. Enjoy the year Lee.

Thank you so much Mark. Happy travels to you too!

[…] of gold, frankincense and myrrh. All these three aromatic resins are widely spread in Oman. It is said that ”the fragrance of frankincense” even fills the air the minute you step off the […]