Bitter-Sweet Sri Lanka

It's just like India on Prozac

THE FORMER CEYLON

emerged from decades of horrifying civil war and the shocking 2019 Easter bombings and yet, on the surface of it, it feels irrepressibly optimistic. Walking alone through villages in the highland tea plantations, I’d often be accosted by beaming schoolchildren, wanting nothing more than to practice their English. Families crammed on to tuktuks puttering along the perilous roads would always gaily wave. When our mini van stopped in a village celebrating a Hindu festival, we were invited to join in the parade. The national flag carries symbols of the four tenets that Sri Lankans hold dear – kindness, friendliness, happiness and community. You see these in practice everywhere. Even on the rare one or two occasions I was approached for a few rupees, it was done so politely I didn’t understand at first what they were asking.

Sri Lanka is only 35 km distance from India across the Gulf of Mannar (and ‘forty miles from Heaven’, according to native tradition) yet, in many ways, it is the un-India – environmentally pristine, still mostly undeveloped, relatively safe and free of hassles, except perhaps when navigating its famously appalling roads. The Sinhalese, forming almost seventy-five percent of the population, are Buddhist, while only fourteen percent, the Tamils, are Hindu. (Although the Buddhists, having no gods, occasionally borrow a Hindu one.) It’s not at all unusual to see a Muslim woman in full black abaya talking to a Hindu woman in a sari and a Buddhist in a flowing white dress.

It’s what I imagine Bali might have been fifty years ago, mostly unspoiled beaches (a few popular ones are to avoided), rice paddies and lily ponds, with the added attractions of dense jungles of wild elephants and leopards, the overgrown ruins of ancient civilisations, graceful Buddhist stupas arising from the landscape, craggy mountain peaks, fragrant spice gardens and tea plantations, all surrounded by the clear, warm waters of the Indian Ocean. ‘Ceylon is a small universe,’ wrote author Arthur C Clarke, who loved it. ‘If you are interested in people, history, nature and art – all the things that really matter – you may find, as I have, that a lifetime is not enough.’

Sri Lankans will tell you that their small nation is experiencing ‘a golden era.’ The terrible civil war that made parts of the country inhospitable for twenty years is over, and the 80,000 dead from the 2004 tsunami have been laid to rest. However, civil rights have not progressed as quickly as they should, and the Easter bombings took another heavy toll on tourism. But the teardrop-shaped island of 21 million people still endures as one one of the most popular tourist destination in the world.

Expat Sri Lankans, who have lived and worked in service and construction industries around the world for those twenty years, have been returning to a country that at last has economic potential. The country’s very first highway was only opened in 2011. Brimming with pride, the locals called it ‘carpet’ because they’ had never had such a smooth ride. You need to experience first-hand the rutted, potholed and crumbling single-lane roads of Sri Lanka and the kamikaze approach of its drivers to understand why a stretch of bitumen would be such a cause for national celebration. Now, many new freeways make the journey more comfortable, and there are more scheduled flights from Colombo to the highlands, cutting several hours from the time it takes to travel to the country’s popular tourist hot spots.

The country desperately needs the infrastructure that is rapidly progressing but for the traveller, quite selfishly, the great pleasure right now is to discover a wondrous land that seems very much untouched by time, where local industries such as cinnamon-shredding, brick-making and tea-plucking are still done in the traditional way, by hand; typewriters are used instead of computers in local courthouses; tailors sit in the dusty streets repairing pants on old Singer treadle sewing machines; schoolgirls walk arm in arm along shady lanes holding parasols; villagers wash their clothes in crystal clear streams and then lay them out to dry on the tops of tea bushes; fishermen sit on poles in the ocean to catch their evening meal, and elephants still do the heavy lifting in teak plantations.

The still-chaotic roads mean it’s not wise to drive around the country yourself, so we chose to travel with the personable Nathan Wedding, the founder of Seven Skies luxury adventure tours, which specialises in guided tours for intimate groups, exploring emerging and fascinating destinations such as Myanmar, Bhutan and Borneo. Nathan, an environmental philosopher and professional sea kayak guide, perceived the need for small group adventures for active and engaged people who nevertheless didn’t want to ‘rough it.’ Nathan’s wife, Clare Turner, a corporate litigation lawyer, runs the show from Brisbane, leaving Nathan free to personally guide most tours, bringing in local experts wherever necessary. The emphasis on all Seven Skies adventures is that you can do as much or as little activity as you wish, which means, in my case one morning, sleeping in and having ‘bed tea’ delivered on a tray when the others are off on a trek up one of Sri Lanka’s highest peaks. (I didn’t feel the least guilty.)

There are eight in our group for the fourteen-day tour, plus Nathan, local guide Arjith, our heroic driver Gamige and the bus boy, Karveen, whose job it is to hand out cool drinks and help Gamige negotiate the narrow roads, which are choked with every kind of vehicle from bullock carts to local buses boasting ‘Semi Luxury Service’ and the occasional goat or cow. (The basic principle of driving in Sri Lanka is ‘whoever gets to the intersection first is right,’ according to Arjith.)

TAILORS SIT IN THE DUSTY STREETS REPAIRING PANTS ON OLD SINGER TREADLE SEWING MACHINES; SCHOOLGIRLS WALK ARM IN ARM ALONG SHADY LANES HOLDING PARASOLS.

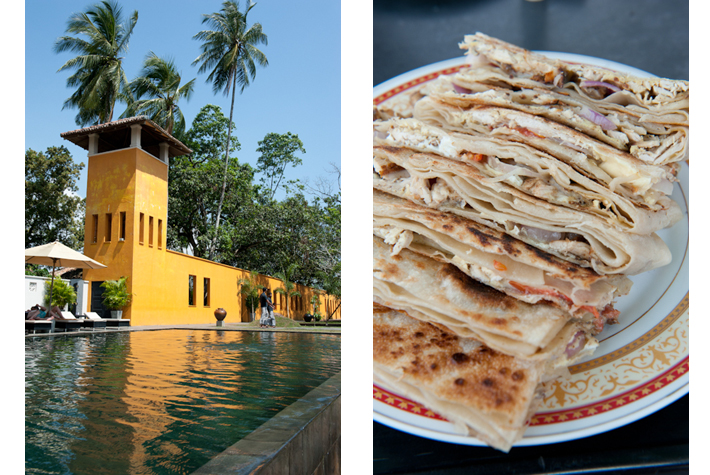

A late night arrival at Colombo’s Bandaranaike airport means we don’t have much time to enjoy our Garden Suite at Wallawwa, a small hotel of ten rooms conveniently near the airport (but so tranquil it feels as if it were a hundred miles away), and set in what was once the manor house of the Head Chieftan of Galle. In the morning we have time for a leisurely breakfast, a swim in the stone-tiled pool and a wander through the two acres of gardens before setting off for the ‘Cultural Triangle’ of ancient Ceylonese cities, a journey made longer than it should be the traffic-choked roads.

Still, the scenery out the bus window is fascinating – paddy fields and jungles, plantations of coconut and rubber, roadside stalls selling sweets made from ‘jaggery’, the crystallized sap of the fishtail palm, villages of half-built houses (the Sri Lankans, admirably, don’t like debt and only finish their houses when they can afford to) and lofty treehouse structures in the fields, which we learn are vantage points from which to throw firecrackers at elephants who might trample the crops.

After stopping for buffet lunch at Kandalama, the rather creepy, brutal modernist hotel rising out of the jungle that was designed by famous local architect Geoffrey Bawa, we arrive at Ulagalla, a resort built around a 116 year-old colonial mansion and surrounded by 78 acres of paddy fields, tropical gardens and lily ponds. Like Wallawwa in Nogombo, Ulagalla occupies a wallawwa, the house of a plantation manager or head man, often bestowed on a local Sinhalese by the British rulers in return for running the plantation and keeping an eye on any trouble brewing in the village.

The secret to traveling in Sri Lanka is to stay wherever possible in one of these beautiful manor houses, some of which have been lovingly restored by a group of rather colourful British expats such as Geoffrey Dobbs, who owns The Sun House and The Dutch House in Galle, Tim Jacobson, who has restored The Kandy House, the 200 year-old former home of the Chief Minister of Kandy, and George Cooper, a descendent of the first Governor of NSW, who owns the resort Kahanda Kanda, set in a tea plantation behind Galle. While no one wants a return to British colonial days, some of the sybaritic pleasures of it are on offer. Often, you sleep in four-poster beds under swathes of mosquito netting, in rooms with wide plank floors, ceiling fans and deep verandahs furnished with rattan chairs. ‘Bed tea’ is brought to your room in the morning and G+Ts are sipped on the lawn at dusk. A game of croquet is sometimes possible for the adventurous.

Ulagalla is the new face of sustainable tourism in Sri Lanka, modelled very closely on the Aman and Six Senses resorts. While the reception, bar and restaurant are situated in the wallawwa, twenty spacious and modern ‘chalets’ with plunge pools (the rooms constructed from wheat straw panels invented in Australia) are dotted throughout the rice paddy fields. You get around on bicycles, electric golf carts or even on horseback if you so desire. Ulagalla operates the largest solar farm in Sri Lanka, harvesting rainwater and growing some of its own produce organically. Seventy percent of the staff is drawn from a 50 km radius and ten boys from local villages have been trained to become naturalists. (Some staff hadn’t encountered cutlery before.)

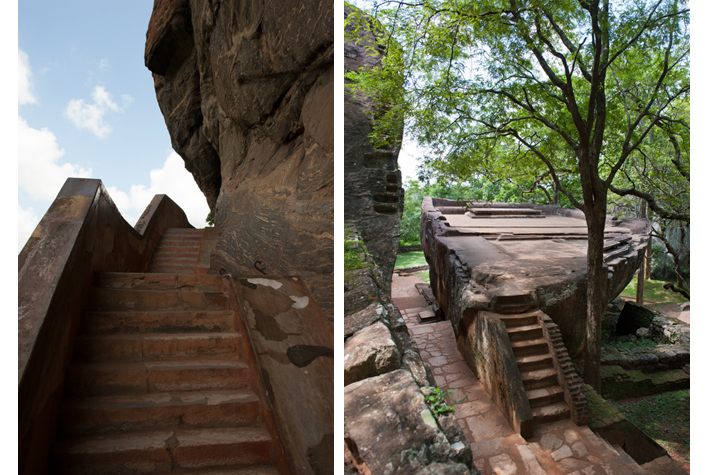

The resort is well situated for us to experience some of the ‘adventure’ part of our trip. We cycle on rough, shady paths through the ruins of one of Sri Lanka’s UNESCO World Heritage Listed cities, Anuradhapura, a kingdom that flourished for 1300 years until the 9th Century BC. We climb the 370-metre high Sigiriya Rock to view the frescoes of naked females hidden in caves and to explore the ruins of the vertiginous city, built by a mad king who, perversely, feared heights. We follow this with a teeth-rattling safari through Eco Park in open-topped jeeps to view elephants in the wild.

After three nights at Ulagalla we travel to Kandy, a busy lakeside city in the central hill country, considered the spiritual heart of Sri Lanka because it is home to Buddhism’s ‘Mecca’, the 16th century Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic. (Kandy is also famous as the place where you can get a good second-hand car.) The British ruled here until 1948 and the small city was the home of the last Ceylonese King. Before we get there, we make a lunch-time detour to visit the home and workshop of Sri Lanka’s most famous batik artists, Ena de Silva, who at 92 years old is one of the country’s National Living Treasures. Local women form a cooperative to produce the beautiful, vivid fabrics, the profits being returned to their villages.

The house is set in exquisite exotic gardens and we wander down a path to a little restaurant, wildly painted with abstract designs, where a feast of twenty-five curries is laid on for us, washed down by iced ginger tea and finished with wattalapan, a scrumptious caramel dessert. Although fabrics are for sale from the small shop, there’s none left today – all have been snaffled by a local hotel for its interiors.

We stay up in the cool hills at The Kandy House, which Tim Jacobsen opened as a hotel in 2005. It’s bliss in the evenings sitting on the lawn sipping our G+Ts with butterflies flittering about (the nine rooms are each named for a butterfly, such as ‘Pioneer’ and ‘Cornelian’.) The next day, we join the pilgrims worshipping at the Sacred Tooth Temple, take a fascinating morning stroll through the former pleasure gardens of the First Kandian King with Dr Pali Pana, who is the leading authority in Sri Lanka on botany, and visit the gem dealer EW Balasuriya & Co to gawk at some of Sri Lanka’s famous star sapphires. The gem mines have been famous since Sinbad’s day and gem merchants still descend on Sri Lanka for inexpensive stones. I’m quite taken with a rare green sapphire but at $550 (a steal, I’m told) it’s not taken with me.

At Peradeniya station we hop aboard the Rajadhani Express in ‘ultra luxury’ carriages for the two-hour trip to Hattan station in the heart of the tea plantations. The train rocks and rattles enjoyably and whenever we pass through a tunnel, there’s a mighty uproar as our fellow travelers lean out the windows and squeal for joy, thrilled with the way their voices echo in the dark.

A FEAST OF 25 CURRIES IS LAID ON FOR US, WASHED DOWN BY ICED GINGER TEA AND FINISHED WITH WATTALAPAN, A SCRUMPTIOUS CARAMEL DESERT.

The Bogawantalawa Valley has the highest annual rainfall in Sri Lanka, perfect for the green budding tea bushes, which produce fresh leave every seven days. The tea plantations are strangely bereft of their tea pluckers, as it’s the annual Sun God festival. The tea workers – women pluck and men work in the factories – are Tamils and each small village scattered through the hills has its own riotously-adorned Hindu temple, with loudspeakers blaring merry dance music across the normally tranquil fields. The Norwood Estate, where we stay for two nights, is part of Tea Trails, five beautiful manager’s ‘bungalows’ dotted through the 500-hectare Dillmah estate. The idea is to hike from one bungalow to the other through the villages and undulating hills, sending your luggage on ahead.

We stay at Norwood and Castlereagh bungalows, which are a ninety-minute hike apart. Part of the Relais & Chateaux group, the four guesthouses are all-inclusive experiences, with personal chefs, a high ratio of attentive staff and complementary hand laundry service. The Executive Chef, Wajira Gamage, proposes a menu each meal, which is adjusted to taste. (We loved the curry banquet and tea-stained chicken.) It’s very pukka to sit on the terrace beside the croquet lawn and be served a tower of cakes and scones and the finest (very) local tea.

The Castelreagh bungalow is perhaps the prettiest, overlooking as it does a silvery reservoir with the tip of a Hindu temple emerging from the flooded valley. If tea is your thing, it’s a real privilege to be guided through the Norwood tea factory with the garrulous planter-in-residence, Andrew Taylor, a descendent of James Taylor who first planted tea on what was originally coffee groves. I now know more than I’ll ever need to know about tea, including how to make it. (Only put cold water on to boil; adding milk or sugar destroys the antioxidants.)

Before we leave this region, the fittest take on the pilgrimage up Adam’s Peak. Some days 100,000 pilgrims or more slowly ascend the 2243 metre-high mountain to worship the footprint of the Buddha in a temple at the summit. It’s one of the holiest sites in Buddhism. The climb is preferably done in the early morning in the dark, the paths lit by flares, so that the pilgrims can greet the sunset when they reach the top. At this moment, a startling, supernatural vision appears – a ‘hologram’ of a pyramid floats between a triangle of mountain peaks, an astonishing natural trick of the light. ‘A wise man does it once, a fool does it twice,’ the locals say of the pilgrimage. Nathan Wedding has done it three times now.

As we drive through the hills to the coast, we pass roadside tearooms promising ‘Friendly Prestigious Service’ and the river where the 1959 movie The Bridge on the River Kwai was filmed. In each village mechanics are busy fixing old cars and photo studios advertise plump grooms in princely outfits and blushing brides dazzling in traditional red and gold. For some reason, Keith Urban is the poster boy for the local barbershops. Just about everything in Sri Lanka is salvaged, from beautiful old doors to rubber tyres. Furniture and the hand-thrown clay pots used in cooking are sold in the open air.

Before we reach Galle, we stop at Lunuganga, the country house of architect Geoffrey Bawa (who died in 2003). It’s now possible to stay in guest rooms in this rambling collection of small houses and pavilions set in acres of rice paddies and lily ponds. Although not far from the popular beach side spot of Bentota, the property feels as secluded as a mythical garden, especially as you’re often surprised by the bust or statue of a classical figure emerging on an overgrown path.

In 1505, Portuguese captains trading spices in Africa and India got blown off course and sought sanctuary in the harbour at Galle (‘place of big rocks’). Discovering Sri Lanka’s rich cinnamon forests they built a fort and stayed. In 1640 the Dutch captured Galle and ruled there until 1796 when they handed the fort to the British without a single shot being fired. These days, Galle is a UNESCO World Heritage city with a mostly Muslim population, reflecting the earliest spice traders who came there from the Arab world. The small city inside the fort is beautifully preserved, with sympathetic renovation of many of the houses – which even include some art deco gems – into hotels, shops, bars and restaurants, while still very much being in the hands of the local residents. The ramparts were built at the beginning of the 18th Century and have protected the city from war and natural disaster, including the 2006 tsunami.

We check into the majestic Amangalla, a member of Aman resorts, occupying the site of the New Oriental Hotel. Part of the building actually dates to 1684, but the original hotel was opened in 1863, making it one of the oldest hotels in Asia (although the Galle Face Hotel in Colombo also claims this honour.) We’ve arrived during the annual Galle Literary Festival and the first person we run into is Tom Stoppard having tea on the wide colonial verandah. We give the festival a miss, though, choosing instead to wander the narrow cobblestone streets marveling at the charming houses and to walk along the ramparts, where some enterprising boys run a business jumping off the high rocks into the ocean for about $AUD10. Galle is famous for its lace makers (they produced the laces for Elizabeth the Golden Age ) and you can buy a hand-made lace nightgown from a hawker for about $15. In the evening, women in black abayas and boys in white thobes stroll along the ramparts after mosque, their garments billowing in the wind.

I’m captivated by a young man making roti in a hole-in-the-wall café. First, he spreads batter on a hotplate to make a thin crepe, then he fills a corner of it with spicy vegetables and lastly flips it into a triangular shape. The owner of the Sunset Café, Maurice, tells me that the boy comes from a family known to be specialists in roti. When I ask to buy a few of the delicious triangles, Maurice won’t let me pay. ‘Because I want you to enjoy them,’ he insists. That night, we eat at Mama’s Café on an outdoor terrace overlooking the mosque and the lighthouse. My curry feast of several dishes costs about $6.

No matter how simple the food in Sri Lanka, it is always delicious, and usually cheap. Seafood is abundant and the Sri Lankans have a sweet tooth, which suits me. I’m especially besotted by the pancakes stuffed with shredded coconut and jaggery that are left as a turndown treat at Amangalla.

Our last day is spent in Colombo, a chaotic city with a romantic history as the one of the major eastern ports for cruise liners in the 20th century. We stay at Tintagel, which was the home of Prime Minister Bandaranaike (who was famously assassinated on the mansion’s front balcony). Hotelier Shanth Fernando once had a decorating business in Mosman, Sydney, and he has restored the mansion to chic perfection, in a dramatic modern style, adding a lap pool and a garden restaurant.

Colombo has a few things to recommend it including the lively Pettah market with its Red Mosque. Sunset drinks on the lawn of the old Galle Face Hotel are a tradition. It’s also worth visiting Sri Lanka’s best-known home design and fashion store, Barefoot. Hand-loomed furnishing fabrics are among Sri Lanka’s best buys.

The schedule for flights to Colombo often means that you arrive and leave in the middle of the night. This gives the illusion that Sri Lanka’s lush and sensual beauty might only be a dream. I have pinched myself but, still, I’m not convinced it was real. I’m afraid I’m just going to have to go back soon and find out.

Sri Lanka has the opportunity to avoid the intrusive, unsustainable development that has all but ruined parts of neighbouring countries like Thailand. However, a number of massive projects, such as a ‘new Dubai’ to be built on an artificial island offshore from Colombo, are planned. Go now.

Just wonderful, green with envy.

John