Playing Cowgirl in Texas

There's more to Fort Worth than rodeos.

Some

little kids want to be cowboys. Some want to be the indians. I always wanted to be Annie Oakley.

I have a photo of myself at age four, standing shyly on the steps of our half-built Melbourne house, in my new cowgirl outfit, a fringed skirt and vest, a cardboard Stetson hat and a holster with a toy gun. I’m missing an essential ingredient – cowboy boots – and there’s no horse in sight. But eventually I got my ride – my father, inspired by my sister and me constantly entreating him for a pet pony, made me a rocking horse on springs, which I still have to this day.

Annie Oakley was probably as good a role model for a young girl as any. She was a superstar in the 1880s and onwards as a sharpshooter in Buffalo Bill’s touring Wild West Show. Born to terrible hardship in Ohio, she learnt to shoot and trap so she could feed her widowed mother and siblings. When she was fifteen she outgunned travelling show marksman Frank Butler in a shooting match. As fans of the musical Annie Get Your Gun will know, Annie married Frank Butler soon after and they began performing together.

Her most famous trick was her ability to repeatedly split a playing card edge-on, and put several more holes in it before it could touch the ground. She used her skills to promote the necessity for women to defend themselves and later in life she was active in women’s rights.

I didn’t know much of this at four. All my information came from the 1950s Annie Oakley TV series starring Gail Davis, which was a completely fictionalized account of Annie’s life. Even so, like Lois Lane in Superman, she was one of the few independent women on television. Or maybe I just liked the costumes.

The TV series is pretty much forgotten, but at the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in Fort Worth, Texas, there’s a display of memorabilia from it, including a photo of Gail Davis looking cute in blonde pigtails. The real Annie Oakley, judging by photographs in the museum, looked quite different. Standing only five foot tall, with long brown hair, she wasn’t nearly as glamorous as TV or cinema portrayed her.

The National Cowgirl Museum celebrates the ‘courage, resilience and independence’ of all the women who helped shape the American West and inducts a new woman every year. It’s nirvana for wannabe cowgirls.

Two elegant staircases lead to three gallery areas, a theatre, hands-on children’s areas, a flexible exhibit space, research library, catering area, and a retail store that sells books, handicrafts and cowgirl costumes for little girls. The Hall of Fame honourees are exhibited in a beautiful space under a domed rotunda. The building is very grand – far from the hardscrabble life some of the women, including cattle drovers and cowhands, lived on the range.

There’s a fascinating section honoring rodeo and trick riding, another relating to ranching, and a further exhibit about the way cowgirls have been represented in dime novels, TV and film. The photographs of daredevil stunts are astonishing, including Nancy Bragg Witner’s ‘Falling Tower’ a standing backbend from the saddle of a galloping horse. If you really want to get into the spirit, there’s a mechanical bull that will toss you around.

Those dang cowboys didn’t stop the cowgirls, however, who staged their own rodeos.

Some of the more outrageous costumes worn by female rodeo and show stars are on display, including a sequined coat and hat worn in the 1920s by Mamie Hafley, whose popular trick was to ride her horse off a fifty foot high platform into a barrel of water just 10 feet across.

The museum also features the snazzy black and silver outfit worn by another showbiz cowgirl I admired, Dale Evans, the partner of Roy Rogers, who, along with his palomino horse Trigger, were the stars of dozens of Hollywood movies and a TV series. Dale was a singer-songwriter and ‘Happy Trails’, her signature song, is one of the musical numbers you can play on the cowgirl jukebox while viewing the exhibition.

Interestingly, the Cowboys Association did not sanction women participating in rodeos, especially after a couple of fatal accidents in the 1920s and 30s. The Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame, housed in an old barn in the historical Stockyards district of town, honours a few women, but they are mostly part of husband-wife rodeo teams or Miss Rodeo beauty queens. Those dang cowboys didn’t stop the cowgirls, however, who staged their own rodeos.

On Friday night at the Fort Worth Coliseum, the site of the world’s first indoor rodeo, there’s a woman’s roping competition among the men’s events. None of the women are wearing sequined coats and cowboy hats. It’s a far cry from 1913 when trick rider Vera McGinness could scandalize the nation by wearing pants instead of corset and bloomers. And the women are very much secondary to the main action. The most visible woman is the cowgirl who rides around the stadium with the sponsor’s flag between every event.

I wondered how many cowgirls were still riding the range today and set out to find one of them.

It’s easy enough to find cowboys. Fort Worth is known in Texas as ‘Cowtown’ because it flourished in the late 19th Century as an essential stop on the Chisholm Trail, the most important cattle drive route to Kansas. The opening of the Texas and Pacific railway in 1876 transformed the Forth Worth Stockyards into a prime centre for the wholesale trade. The Livestock Exchange building is still an important venue where cattle are bought and sold.

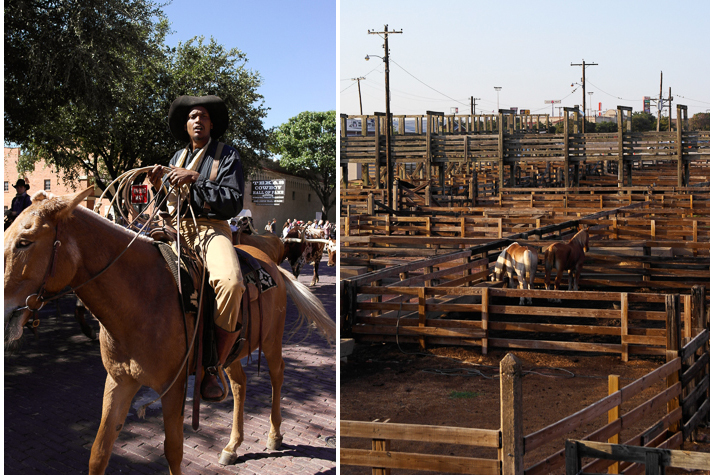

Each morning and afternoon, a herd of sixteen Texas Longhorn steer are mustered through the historical district for tourists, the world’s only twice-daily cattle drive. About a dozen drovers regularly usher the herd a few blocks and I’d been told one of them was a woman. I am curious to meet her.

Fort Worth was once a rough old town, hostile to women, and what is now the CBD was once known as Hell’s Half Acre, populated by brothels and honky tonks, the scene of many bar fights and shoot outs. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid lived and ran their Hole in the Wall Gang out of Fort Worth. The Stockyards hotel on Exchange Avenue in the historical district has a Bonnie and Clyde suite, where the Texas-born outlaws stayed when on the run in 1933.

Exchange Avenue looks pretty much as it might have looked in the 19th Century, although the posted verandah shops nowadays sell souvenirs and expensive jewelry, and there are wine bars and art galleries instead of roughneck saloons. Booger Reds, a local bar with saddles as bar stools and a giant taxidermied buffalo butt over the bar, perhaps comes closest in spirit to the good ole days.

Further down the avenue near the Livestock Exchange Museum, the cattle are kept in pens, which have viewing platforms around the perimeter – a wholly authentic eau de cow dung pervades the district. There’s usually a cowboy or two on horseback ambling down the road at any given time.

‘Nothing is more therapeutic than riding a horse, chilling. It’s too cool.’

And they love to chat. Strolling down the street, I meet two friendly gunslingers – Lyle Holliday, a fifth generation descendant of Doc Holliday, of Gunfight at O.K. Corral fame, and Jim ‘Creek’ Tipton, whose descendants also date back to when the west was wilder. Both men perform in the Legends of Texas Gunfight, held morning and afternoon during summer inside Stockyards Station. Lyle Holliday’s faded blue eyes and faded blue neckerchief are testament to the fact that he’s the real thing, with bona fide cowboy credentials. He tells me that being a cowboy is more about mending fences than riding your horse all day long.

While I’m waiting for the muster, I shop for cowgirl gear. M.L. Leddy’s, a saddlery and bootmaker on the corner of Exchange Avenue, has been providing custom made boots, saddles, belts to Texans since 1922. It takes about a year for a pair of customised boots, which can be measured-up in store, although there are plenty to select off the rack. It’s worth a visit to peruse the amount of gear a serious drover needs – chaps, heavy gloves, spurs, ropes, bedrolls as well as Stetson hats and saddles.

Cowgirl style includes fringed buckskin jackets and skirts, embroidered blouses, silver and turquoise jewelry and neckerchiefs. If you’re in any doubt, Cowgirl magazine has all the info for fashion-forward gals.

But drover Brenda, who is riding with the cattle herd, wears little of this. She’s dressed in a beaten up hat and boots, with a vest over pants and shirt, apart from her long hair nothing different to what the cowboys wear. That’s how it was in the 19th century, she explains. ‘Them ugly old guys never cut their hair so a girl could fit in real easy. If they could rope or ride they weren’t recognized.’

Sitting high on her palomino Charlie she’s happy to give me a lesson in how the it was in the old days. Cowboys and girls always rode for a brand (the Fort Worth Herd’s brand is a Longhorn steer with a running ‘F’) and it took about eight people to drive the cattle the 3000 miles to Kansas City, over about four months. Per head, the steers were only worth about $1 in Texas, but could fetch $40 in Kansas, which is why ‘you never ate your income’ traveling instead with a chuck wagon full of dry goods.

The drovers never carried guns – a gun going off could cause a stampede. Were they afraid of indians? She shrugs, ‘You were dead by the time you were thirty anyway.’

Now that I’ve been ‘historized’, as she calls it, I ask Brenda if she had always been a drover. She shakes her head. ‘No ma’am, I was a city girl. I raced cars, was a mechanic. Got wise and got me a horse. Nothing is more therapeutic than riding a horse, chilling. It’s too cool.’

Fort Worth’s cowgirl-in-chief is mayor Betsy Price, a former tax assessor who turns up for a meet and greet in Sundance Square in a pink shirt, black jeans, cowboy boots and an impressive belt buckle, having just come from shooting clay pigeons on the range. ‘My gun was hot,’ she boasts.

A straight-talking kind of gal, her horse is a mountain bike, which she has been riding enthusiastically for 25 years. When she became mayor in 2011 she instigated ‘rolling town halls’ where locals are invited to ride with her and discuss issues while they cycle. This is all part of a Fit Worth initiative to promote healthy living – a tough task in a state where even my breakfast order for porridge prompts the question, ‘Do you want bacon with that?’

I learnt quite a lot about cowgirls from my visit to Fort Worth. I did some line dancing and ate ‘cowboy cuisine’, which included fried calf testicles. Life on the range and at the rodeo was tough, more so for women than men. Riding with the cattle meant months at a time spent in the blazing sun with only dry food from a chuck wagon as nourishment.

I’m glad I’ve still got my rocking horse. I think I’ll stick to that.

WHERE TO STAY

Well-located in downtown Fort Worth and opposite the city’s lush Water Gardens, the Omni Fort Worth is a large, well-appointed, modern hotel, popular with conventions, that has plenty of western charm with a ranch-style lobby, a great swimming pool deck and a free shuttle service around town.

HOW TO GET THERE

For travellers in Oceana, Qantas makes Dallas Fort Worth extremely accessible with its comfortable A380 service, flying nonstop to DFW from Sydney. DFW is located less than four hours away from every major US city and seamless connections can be made with Qantas partner American Airlines to over fifty destinations in the USA, Mexico and Canada.

Lee Tulloch was the guest of Qantas and VisitDFW.